These Educators Grew Up Earlier than DACA. Now Their College students Face the Similar Obstacles.

[ad_1]

Even when she was a 9-year-old, not too long ago arrived to Nevada from Mexico along with her household, Liz Aguilar knew she was going to school. She informed her dad and mom that she didn’t care about having a quiceñera, the large coming-of-age celebration that Latino households host when a lady turns 15. Put that cash away for faculty, Aguilar informed them.

So the quiceñera by no means occurred. However neither did the school fund.

Aguilar had a secret she was holding shut, one which made her faculty dream appear extra unimaginable the nearer she received to highschool commencement.

She was undocumented.

It was earlier than the Obama administration launched the Deferred Motion for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA for brief) in 2012 that gave some immigrants who have been dropped at the U.S. as kids safety from deportation, together with permission to work and go to school.

“As soon as I graduate, I’m terrified. I’m seeing how a lot my dad and mom have struggled, and I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Aguilar remembers.

Fortunately for Aguilar, two issues occurred shortly after. First, her highschool sports activities coaches felt she had potential to do effectively in faculty, each academically and as an athlete, and so they went to work guiding her by the admissions course of (extra on that later). Second, unbeknownst to them, Aguilar utilized as quickly as she may when the Division of Homeland Safety initiated the DACA program in summer season 2012.

Aguilar finally took half in Educate for America, and he or she nonetheless teaches at the highschool the place she received her begin, working with college students who’ve not too long ago arrived within the nation.

Eleven years later, she now finds herself in an uncanny place.

Aguilar has turn out to be a sounding board for immigrant college students who, as a result of they lack everlasting authorized standing within the U.S., face the identical hopeless post-graduation outlook that she had as an adolescent. Folks on this scenario typically establish as “undocumented,” referring to the truth that they don’t have official kinds granting them permission to dwell within the nation.

Aguilar is one in all about 15,000 academics within the U.S. who’re undocumented however are in a position to work because of DACA safety, granted earlier than the coverage entered authorized limbo most not too long ago in 2021. They now have gotten mentors to college students whose lives look very like theirs did greater than a decade in the past — besides now the hope of aid from a coverage like DACA is dim even amongst its proponents. A federal decide is mulling over this system’s legality, and new functions haven’t been accepted for the previous two years.

So for now, Aguilar advises these college students as greatest she will.The trainer helps with their sensible questions, like the way to pay for greater training. She additionally listens with empathy as they specific their fears.

“They are saying, ‘Miss, I don’t know what to do, I’m scared, I do not even know if I can go to school,’” Aguilar says.

Caught in Limbo

In a not too long ago launched report, immigration advocacy group FWD.us led with a startling determine: Many of the 120,000 highschool college students dwelling within the nation with out authorized permission who’re graduating this yr are ineligible for DACA.

That’s not simply because new functions have been paused.

DACA has a number of time-related constraints that restrict who’s eligible for its safety. A type of necessities is that candidates should have “repeatedly resided in the USA since June 15, 2007.”

It’s been virtually 16 years since that cutoff date, which was earlier than lots of the estimated 600,000 younger immigrants missing everlasting authorized standing who are actually enrolled in U.S. public faculties have been born.

So to qualify for DACA, this yr’s highschool seniors wanted to have arrived within the U.S. earlier than they have been 2 years previous.

“However now, solely a fifth of this yr’s undocumented highschool graduates could be eligible for immigration aid by DACA underneath present guidelines,” the report says. “By 2025, no undocumented highschool graduates might be eligible for DACA underneath present guidelines.”

A few of these college students are in Aguilar’s classroom now. They’ve the identical query after studying that she went to school after receiving DACA safety: “How did you do it?”

“Usually the way in which this dialog begins is I’m not afraid to share with my college students about my standing, as a result of rising up I felt like I couldn’t share that with anyone,” Aguilar says. “I need you to know I may help you work it out.”

Whereas Aguilar confronted hurdles on her personal path to school, she discovered herself with advocates after she ran observe her senior yr of highschool and impressed the coaches along with her expertise.

“They noticed potential in me, however they didn’t know I used to be undocumented,” Aguilar says. “They launched the thought of going to school and competing, however I used to be like, ‘I can’t do this.’”

That modified after she was granted DACA safety, and her coaches helped her make her technique to neighborhood faculty, providing help by the applying course of, determining the way to finance her research and even which lessons to decide on. She went on to earn her bachelor’s diploma in historical past after which her grasp’s diploma in curriculum and instruction with a concentrate on English language arts.

One factor Aguilar by no means tells her college students is that the method of going to school might be simple. However even after they go away her class, she’s nonetheless of their nook — identical to the educators who have been by her facet in highschool and past.

“It’s going to be twice as arduous as anyone else, nevertheless it’s attainable, and I’m the strolling definition of it,” she tells her college students. “I nonetheless have college students from three years in the past, and we’re nonetheless figuring it out collectively.”

A Trainer Who Understands

José González Camarena is a former center college trainer with Educate for America and, like Aguilar, grew up undocumented within the U.S. He’s now the senior managing director of the Educate for America Immigration and Training Alliance.

González Camarena says that roughly 400 educators with DACA safety have gone by the instructing program since 2013. Some doubt whether or not they have a future in instructing — or any occupation.

“I hear this from quite a lot of the educators, and I skilled this myself, considering, ‘I’m getting this diploma to what finish? What am I going to do?’” he says. “A few of those self same sentiments that Liz was sharing, quite a lot of faculty college students really feel that now with the context of DACA. I believe it’s incumbent on all of us within the training house to share what these alternatives are.”

Nevada is likely one of the states, González Camarena explains, the place an individual missing everlasting authorized standing can get their instructing license even with out DACA safety. Whereas they’ll’t be employed straight by a faculty district, they’ll work as an unbiased contractor.

If González Camarena is keen about sharing the choices which might be nonetheless out there for college kids and educators dwelling within the U.S. with out authorized permission, it’s maybe as a result of — like Aguilar — he was as soon as a type of college students who graduated highschool earlier than the launch of DACA. At the same time as a teen in California on the time, which allowed college students like him to pay in-state tuition charges, the price put faculty out of attain for him and his household.

And once more, like Aguilar, a coincidence modified his plans.

“Fully by luck, I got here throughout a weblog of undocumented college students who have been sharing their [college] experiences anonymously on-line,” he remembers, “and I utilized to 3 personal faculties as a result of I heard tales of undocumented college students at these establishments.”

A type of faculties, the College of Pennsylvania, provided González Camarena a full scholarship. It’s there that he earned his bachelor’s diploma in economics from the Wharton Faculty.

Whereas he was working as a sixth and seventh grade math trainer, the Trump administration made its first try to finish DACA. A few of his college students feared on the time that such a transfer would hurt their households and, right this moment as younger adults, some have been unable to enroll in this system themselves. (González Camarena is a former DACA recipient and has since gained residency.)

“In these years specifically it was necessary for me to share neighborhood sources, know-your- rights workshops, equipping them with the fundamentals of, ‘You could be undocumented, your standing could also be XYZ, however you continue to have rights,’” he says. “I believe these conversations ought to be taking place lots sooner than center college with college students and fogeys.”

Having a trainer with firsthand expertise navigating these challenges could make an enormous distinction as a result of college students can really feel hesitant to take these questions to oldsters, who’re immigrants themselves and might discover the school utility course of simply as daunting as their kids.

“They do not wish to put that strain on their dad and mom or make them really feel a sure method as a result of they made sacrifices to come back to this nation,” Aguilar says. “You’ve got that stress of being undocumented, after which you have got the opposite stress of — your dad and mom are usually not essentially ready that can assist you with [college] both.”

Aguilar says she feels lucky that her college students really feel comfy sufficient to method her with not simply questions on faculty but additionally bigger-picture inquiries about “how can they accomplish their desires.”

Paying It Ahead

When recalling their very own experiences as excessive schoolers, the feelings that Aguilar and González Camarena describe are painful.

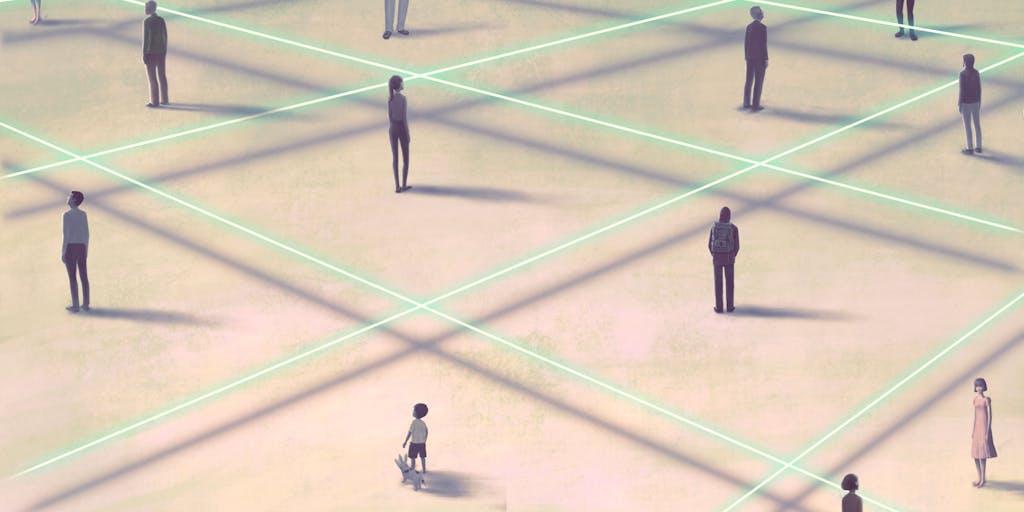

A time filled with anxious pleasure for thus many teenagers was, for them, filled with dread. Like stepping out on a cliff within the fog, not understanding whether or not their ft would land on a bridge or slip into empty house.

What the pair describe, even a decade or extra faraway from their experiences, feels overwhelming. Even claustrophobic.

“Considering again to it, I used to be a really depressed teenager, and it had lots to do with my standing,” Aguilar says. “Even now I’m virtually 30, and there’s by no means been a way of safety. I don’t know what’s going to occur to me, and that’s why in highschool I used to suppose, ‘Have a look at how profitable I’ve been in operating, however why does this matter?’ That’s all I can consider, ‘There’s nothing there.’ It was only a very unhappy time for me.”

Right now, many college students on this scenario — or these with DACA safety, not less than — are extra outspoken about their immigration standing. Certainly, it looks as if a necessary a part of their advocacy.

However the undocumented teenagers that Aguilar mentors are simply that — teenagers. Simply as she did in highschool, they’ll really feel powerless over the long run.

Aguilar thinks of 1 pupil she coached in volleyball this previous college yr, who had set a purpose of going to school or turning into an authorized HVAC technician. These plans have been stalled as a result of though he utilized to the DACA program two years in the past, he didn’t make it in time earlier than new functions have been stopped.

“He sits there and he stares out into house and he’s like, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do,’” Aguilar says. “They ask me how I did it, however what I emphasize is that although I’ve DACA, we’re nonetheless preventing for them. I’m nonetheless preventing for them as a result of I need them to expertise what I’ve had the advantage of experiencing.”

[ad_2]